Below we have descriptions of some of our recent research projects.

The modern world is a noisy place; most of the time listeners are trying to hear a single voice while being bombarded with aural distractions — other people talking, traffic noise, music, and all the other auditory freight of modernity.

This is hard enough for adults – but young children are trying to learn their native language in this environment! Much of the time, children hear language in noisy settings - For example, a caregiver may be talking to an infant while other siblings are playing in the next room. Children’s classrooms are likewise noisy, with the sounds of coughs, shuffling papers, and shifting bodies, but children are expected to be able to ignore that noise in order to learn history and math. How do infants and children learn in these types of noisy environments?

We are investigating questions about how children understand speech in noise, how they learn new words in noise, and the types of noise they find most distracting. We are also investigating whether experiencing more noise helps children learn to accommodate it, or just makes learning harder.

So far, we have discovered that:

Why would a language lab study concussion? Well, a concussion is an injury to the brain that makes it harder to think and use language. Moreover, we don’t have good ways to “see” these types of injuries to your brain. If you break a leg, we can see the break on an x-ray. But you can’t see if the brain is hurt on an x-ray. Each year nearly half a million children go to the hospital with a head injury – but young children often cannot tell us when they aren’t thinking straight. So we have been developing a set of language tests that can help us identify when a young child has a concussion, and when they have healed enough after a concussion to be ready to return to school.

We have also been examining how concussions impact language in adults as well, looking particularly at women (such as roller derby players!) and middle-aged adults, since most of the existing research has focused on football players and active military, individuals who may be in different physical shape than most of the population.

Nothing is quite as maddening as knowing the right word or name and not being able to come up with it-- and often it just pops into our head later, when it's too late.

Each of us knows tens of thousands of words, and in order to speak, we need to find the right one in fractions of a second. So maybe the real question is-- why don't we have tips of the tongue more often?

Some people do have them more than others-- individuals with language impairment or learning disabilities, people who have recently suffered a concussion, and even women during pregnancy or menopause, all report having far more word-finding problems than others.

Our lab has studied the types of words that cause these problems, as well as things we might be able to do to avoid them.

We are part of the Learning to Listen project at the University of Maryland, and collaborate with the Maryland Cochlear Implant Center of Excellence.

Cochlear implants (or CIs) are prosthetic devices that provide the perception of sound to severely hearing-impaired listeners, including young children.

Language comprehension and speech production are often difficult for children with cochlear implants. Our goal is to better understand how children with cochlear implants perceive and produce speech sounds so we can develop better interventions.

Why is language so hard for these children? In part, the problem has to do with the limits of the technology – implants cannot transmit the full speech signal. But much of the technology is based on work with adults, even though we regularly implant infants as young as 12 months of age. If we better understood how children interpret the signal from a CI, we could design better implants or interventions suited directly to children’s needs.

Our lab has been conducting a number of studies examining how well children with normal hearing perceive speech that simulates that heard through a cochlear implant. That is, how well children can compensate for “partial” (sparse) auditory signals. This work is in collaboration with other researchers at the University of Maryland, at UCLA, and at BoysTown National Research Hospital.

Most of the world’s population knows multiple languages, and bilingualism (or multilingualism) brings with it many benefits. But how does switching between languages impact learning? Should parents try and stick with a one-parent, one-language approach with their young children? Should second-language teachers switch back-and-forth between languages in classroom, even in the middle of sentences, or should try and use an immersion approach, using one language more consistently? These are important questions, and ones we are trying to answer. We are investigating how language switches impact both adult learners’ and young children’s understanding, learning, and attention.

No two people speak the same way, and some differences can be quite drastic. How do adults identify that didjuh and did you both mean the same thing? How does a child come to realize that bat and pat mean different things, but car spoken by someone from Chicago means the same thing as caah spoken by someone from Maine? As our society becomes more mobile, we are increasingly faced with speakers whose accents differ from our own; although understanding such speakers may cause noticeable decrements in normal conversation, difficulties often become even more apparent when the listening conditions become poorer (as over a telephone, or in a noisy environment), or in high-stress, emergency situations.

Examining these types of problems is critical because it is exactly these tasks that cause the most difficulties for listeners who suffer any form of language or hearing impairment.

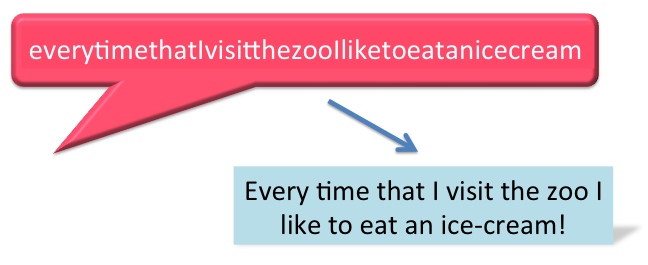

Have you ever listened to someone speaking a language you don't know? Often, it sounds like they never stop to breathe – that they don't have any pauses between words. In fact, English is no different: speakers do not put breaks between words when they talk (unlike in this written text)! But because we know the language, we can identify where the breaks should be, and we insert them on our own. This is referred to as "segmentation", and understanding how listeners do this is a major question in the field of speech perception. Now imagine what it must be like for a young child who hasn't yet learned their native language. Our lab is exploring what types of information listeners use to help them identify the individual words in the speech signal.

BITTSy is a testing platform that allows researchers to design experiments for young in a uniform manner anywhere across the world, and to use multiple testing paradigms with the same laboratory setup. This allows to researchers to better collaborate, to compare results across labs, and to facilitate our understanding of early language development across diverse circumstances. Visit our BITTSy landing page to learn more about this system!